Chimborazo

So, it turns out that this summer I found myself in the lucky situation to be admitted to the Gene Goloub SIAM Summer School 2024 on Randomized Techniques for Inverse Problems in Quito, Ecuador. To spend some more time exploring the country and its culture, I immediately made sure to extend my stay in Ecuador for a couple of days after the school. The goal was clear: summit Ecuador’s biggest mountain, the 6263m/20548ft high volcano called El Chimborazo. This volcano wasn’t exactly unfamiliar to me. For my German final exam in high-school, I’ve read the novel “Die Vermessung der Welt” written by Daniel Kehlmann, in which he tells the story of Alexander von Humboldt, a Prussian scientist and explorer during the early 19th century, who, among other things, attempted an ascension of the Chimborazo volcano. At that time, this volcano in the center of Ecuador was thought to be the highest mountain in the world. Due to strong symptoms of altitude sickness and extreme temperatures, he unfortunately had to abandon his expedition.

The west-side of the Chimborazo

The west-side of the Chimborazo

Acclimatization

Clearly, the altitude would be the biggest obstacle on this volcano. Except for a short climbing section and the steep glacier, there are no technical difficulties to tackle. During the summer school, frequent morning runs in the Itchimba park (2950m/9678ft) with Alex, Esther, Liam, Maria and others before classes; a fun hike to the Rucu Pichincha (4784m/15695ft) with Esther, Robin and Max; and another one to Ilaló (3188m/10459ft) with Esther, Liam, Maria, and Troy have helped me get used to the higher altitude.

On the summit of the Rucu Pichincha (4784m/15695ft)

On the summit of the Rucu Pichincha (4784m/15695ft)

On Saturday morning, August 3, the adventure could begin. After many sad goodbyes to the amazing friends I’ve made during my stay in Quito, I took a 3.5h bus ride to Riobamba and then went by taxi to the entrance of the Reserva de Proteccion de Fauna del Chimborazo. Starting from there, I slowly hiked up to the Refugio Carrel (4850m/15912ft), where I would be spending the night. Since I arrived there a bit earlier than expected, I used the occasion to go up to the Refugio Whymper (5030m/16502ft), which is now abandoned, since most of the routes starting from there are no longer frequented due to rock-fall hazard.

The abandoned Whymper Refugio with the Chimborazo summit in the background

The abandoned Whymper Refugio with the Chimborazo summit in the background

After coming back down to the Refugio Carrel, I was served a potato-soup, rice, lentils, and some pork. Despite there being no electricity, the food was outstanding. Unfortunately, it turned out that I was the only person staying at the Refugio that night. So I enjoyed the beautiful sunset and then headed straight to bed to try to sleep as long as possible. But that is easier said than done. My heart rate was noticeably elevated and every couple of minutes I impulsively gasped for air. Out of the eleven hours I’ve spent in bed, I must have slept at most three. But that didn’t hinder me embarking on my planned acclimatization hike the next morning.

The Refugio Carrel (4850m/15912ft); the starting point for the climb

The Refugio Carrel (4850m/15912ft); the starting point for the climb  Memorial plaques for the many people who have died climbing Chimborazo

Memorial plaques for the many people who have died climbing Chimborazo  Sunset as seen from high above the clouds in front of the Refugio Carrel

Sunset as seen from high above the clouds in front of the Refugio Carrel  The last sun rays illuminating the west-face of the Chimborazo

The last sun rays illuminating the west-face of the Chimborazo

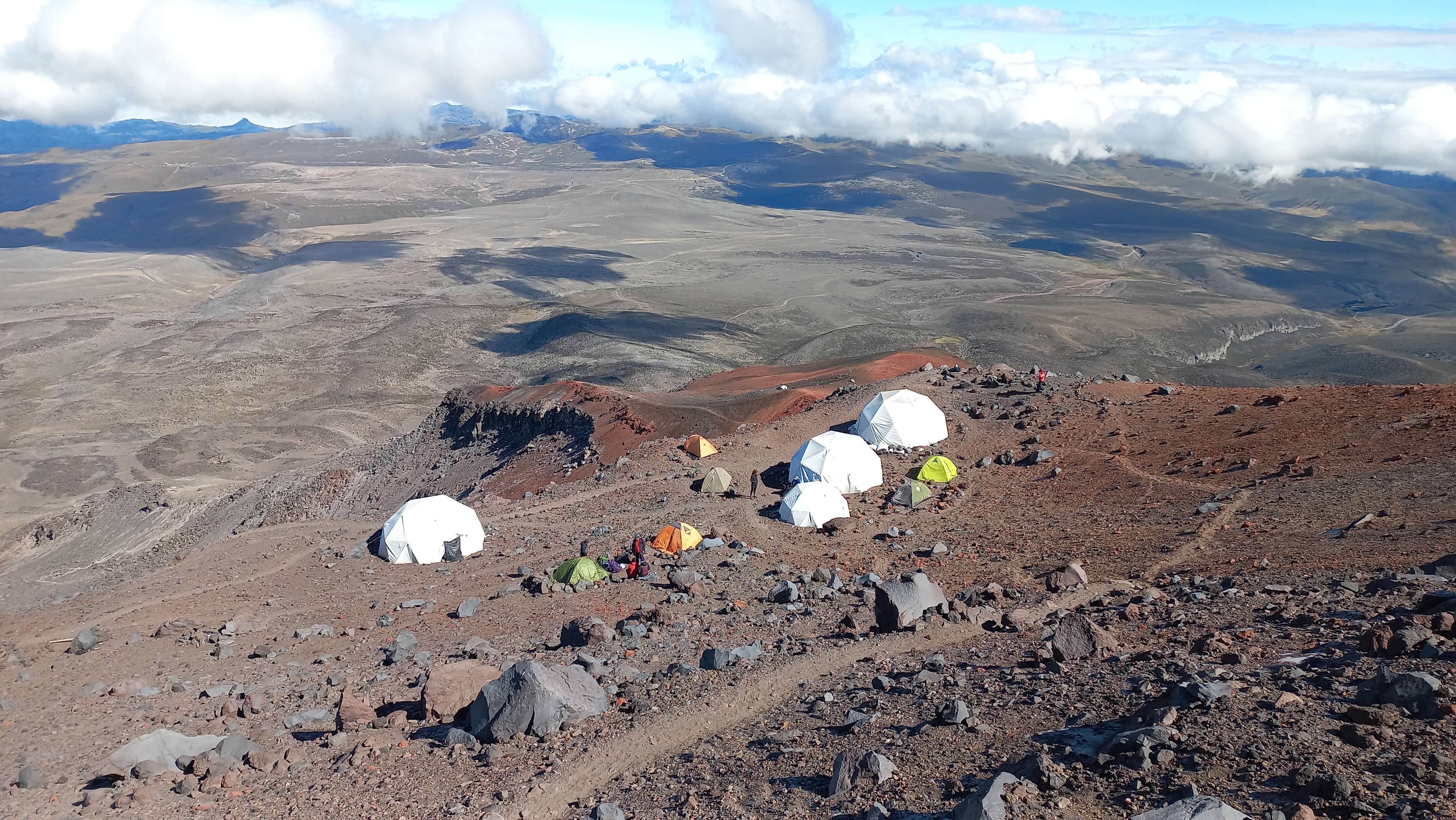

Seeing it get brighter outside in the early morning of August 4 was a big relief for me. Finally, I could get out of bed and go explore the scree-slopes of the volcano. Without even waiting for breakfast to be served, I headed outside and started my hike to the Chimborazo high-camp. After a short traverse through a rock-field and following the west-ridge of the volcano, I’ve reached the high-camp (5310m/17421ft). While it is possible to start the climb from there, I chose not to, because it was quite a bit more expensive than staying in the Refugio Carrel, and seemed significantly less comfortable. And sleeping at 5310m/17421ft altitude seemed impossible to me. The mountain guides there invited me to have a look inside the breakfast tent, where a Dutch couple was eating after they had to turn around due to exhaustion at around 6000m during the night. Clearly, summiting this mountain is not a guarantee. I went outside and boiled some water to prepare a lyophilized meal for breakfast: potato and bacon. After that, I stumbled around a bit more in the high-camp, and went up a bit higher (~5500m/18000ft) to inspect the glacier entrance. That’s when I saw two climbers, a guide and a guy from the US in his 20s, approach the high camp. The US guy looked more dead than alive; another victim of the mountain.

Chimborazo high-camp

Chimborazo high-camp  Cooking my well-deserved breakfast in the high-camp

Cooking my well-deserved breakfast in the high-camp

Being content with my acclimatization progress so far, I went back down to the Refugio Carrel, where they’ve already almost dispatched a search-party, since I was neither there for breakfast, nor, more importantly, did I pay them for the stay yet. After having settled my debts, I hiked back down to the entrance of the Chimborazo reserve. From there, I was supposed to find a ride to the Chakana lodge (3970m/13024ft), where I would spend the night to rest before summit day. However, people did not exactly queue up to take me to my destination, hence why I had to walk most of the way there along a road which was littered with pot-holes. After intruding some private properties to ask for directions, I finally arrived at the Chakana lodge, where I was shown my room for the night: A cozy two-bed room with toilet and shower, and best of all, a direct view on Chimborazo. I spent most of the afternoon preparing my gear, which included re-attaching a loose thumb on my light gloves with a couple of needles I had lying around in my first-aid kit. Potato soup, rice, pork, and an avocado were served for dinner. Delicious, but unfortunately also there I ended up being the only guest that night; Ecuador’s tourism seems to be seriously tanking due to the recent political issues in the country.

Chakana lodge

Chakana lodge  The cozy dining area in the Chakana lodge

The cozy dining area in the Chakana lodge

After a relaxing sleep, which was merely interrupted two or three times by an orchestra of barking dogs outside, I spent most of the morning of August 5 in bed reading and watching the Olympics. Femke Bol carried the Dutch mixed 4x400m relay to gold, and Alice D’Amato was the only gymnast able to show a clean routine on beam. Cereals, ham and cheese sandwich, melons, and scrambled egg were on for breakfast. With the cloud-grazed Chimborazo in view, I did my last mental preparations and cooked myself a lyophilized pasta Bolognese for lunch, after which Paul picked me up with his car. Paul, a 51 year-old father of three, whom I’ve gotten into contact with thanks to a friend, was going to be my guide for the climb. Yes, you are not allowed to climb Chimborazo without a guide, and no, if you don’t climb this mountain multiple times per year, you are not going to find the route on the glacier. Period. After some chit-chatting we were back at the Refugio Carrel, which would be our starting point for the adventure. In the later afternoon we were served potato soup, chicken, fries, and salad for dinner. There was another man with a guide who would also be attempting the climb that evening. With the ambitious goal of trying to sleep, I went straight to bed.

Layout of all the gear I packed for the expedition

Layout of all the gear I packed for the expedition

Climb

My alarm clock would have been set to 10:30pm, but I could have done without, since I did not sleep a single second that evening. Too big was the excitement for summit day. I quickly put on my clothes and harness, and washed down some cookies with coca tea. At 11pm, we left the Refugio. The fog was so thick and humid that we could barely see 10m/30ft in front of our head-lamps. While August 6 creeped up on us, we took the same old path I took the day before to reach the high-camp. No one seemed to have been at the high-camp that night. Once we arrived there, it started ice-raining. I wanted to fetch my rain jacket from the backpack, but quickly realized something had gone wrong. Both my rain and down jacket were soaking wet. One of my water bottles must have leaked. While the rain jacket did a good job at keeping its inside dry, the down jacket was lost. With it, the summit is lost with the least amount of wind up there, which usually drops the perceived temperature to -20°C and lower. You can be sure that I shouted one or two appropriate swear words into the dark. We started a long traverse along a rock-band, but immediately had to put on our crampons to avoid slipping on the wet rocks and residual ice. After a while we reached the crux of the route: A 5m/16ft wall of brittle volcanic rock, which had to be climbed with ice-axe and crampons to avoid slipping on the frozen rocks. Easier done than said, we made our way up a steep scree-slope to enter the glacier at around 5600m/18372ft. The conditions were absolutely outstanding. The ice was rock-solid, grippy, and it was completely wind-still. After an initial traverse to the left, we kept going up the glacier in an almost perfectly straight line. The glacier was very steep (35°), and every now and then we had to hop over a crevasse. After what felt like hours of front-pointing up the monotonous white slope, I pointed up my head-lamp, and was confident I could see the slope flatten out: the summit is near. However, that hope was shattered when Paul told me we were at 5900m/19356ft; not even halfway up the glacier. Classic. Around that point I also started having a weird feeling in my left quadriceps, hence why I started varying my crampon positioning to distribute the load to other leg muscles. I started perfectioning a technique where I was basically placing my feet with my toes almost pointing down the slope while going up; luckily no one was there to judge me on this one. Anyway, after an eternity we finally reached the Cumbre Ventimilla (6223m/20416ft) at 4:42am. I was extremely happy, but started noticing that I was getting very weak. I had no idea why. I was regularly fueling on crackers and cereal bars, so there shouldn’t be an issue with that. At just 40 meters higher, the main summit was now literally a stone-throw away, but in my current condition and without down jacket, in case we were suddenly surprised by wind, I didn’t want to risk it. I told Paul that I’d be glad to turn around, but he insisted that we should go to the main summit. The conditions were absolutely perfect, and we were 2 hours ahead of schedule. Therefore, we started walking a bit down towards the main summit. Just before the slope picked up again, I was overwhelmed with fear. My legs started getting quite weak. Certainly, my energy levels were still enough to make the main summit, but what about the way back? I stopped Paul and told him that I’m not sure if it’s a good idea to keep pushing. I told him that in Switzerland I wouldn’t hesitate a second to continue, because there’s always the option to call the helicopter, which will fly you out of the situation. I asked him what he’d do if I suddenly collapsed up there. He didn’t seem to be worried at all, but I’m afraid that at over 6000m/20000ft, dragging a climber with all his gear back up the 20m/65ft slope to the Cumbre Ventimilla is basically impossible, even for someone used to the altitude. In this panicked realization, I insisted that we turn back immediately, which we did, and subsequently started the down-climb. This was the worst part of the experience. After just a few steps, my stomach started hurting atrociously, and I could barely take steps anymore. I had to lie down multiple times in an effort to try to let my stomach settle: No success. We advanced very slowly, and crossed the other rope-team at around 6000m. They were still looking quite strong, but were a bit late. The sun was about to rise. After an unexciting descent in immeasurable pain, we finally returned to the high-camp. There we took off our crampons and walked back down to the Refugio Carrel. It was 9am. All pain was suddenly gone.

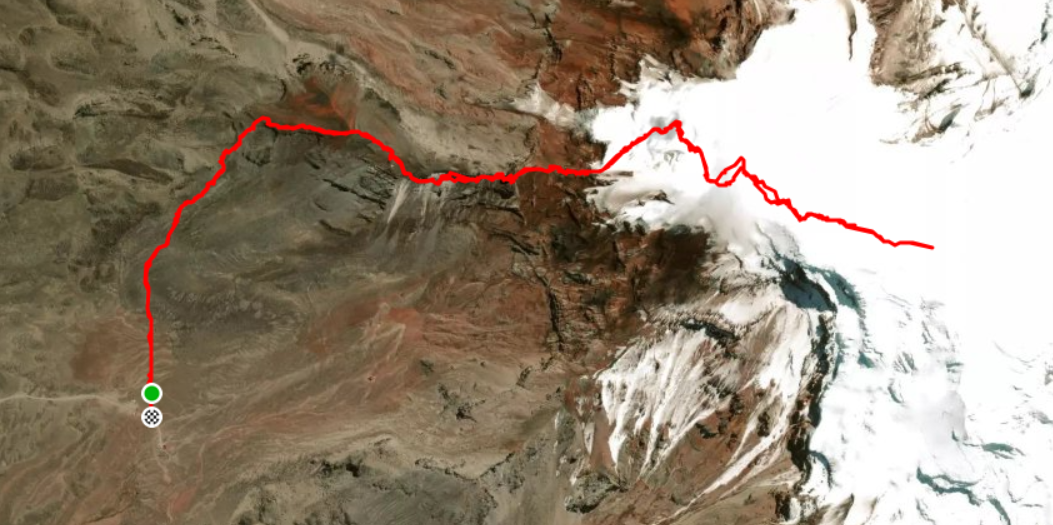

The GPX track recorded during the climb

The GPX track recorded during the climb  View towards the glacier entrance (photo taken the previous day)

View towards the glacier entrance (photo taken the previous day)  Back at the Refugio Carrel after a long night

Back at the Refugio Carrel after a long night

Debriefing

So what happened? Frankly, I can’t tell. But I have a very strong suspicion: My fueling strategy wasn’t thought through well enough. Cereal bars are my go-to food for trail-running and mountaineering. I have never had problems with them, and have the timing for re-fueling boiled down to a science. However, during the climb, I noticed that the cereal bars were completely frozen when I grabbed them from my backpack. This, and the fact that they are quite complicated to digest, made up the perfect cocktail for indigestion, which deprives the body of the energy and causes pain in the stomach. Since I’ve been mostly relying on cereal bars for fuel, these calories must have gone lost in the calculus, and therefore, combined with the extreme altitude, must have caused my weakness. The bobbing around of these undigested cereal pieces in my stomach must have been what caused the stomach pain on the way down.

In hindsight, I should have done more research on high-altitude nutrition. It was a big mistake to suppose that a low-altitude fueling strategy could directly be translated to a high-altitude setting. Still, the whole experience was extremely fun, and I could learn a lot about myself, mountaineering, and Ecuadorian culture. I’m thankful to have made it back completely unharmed and still with a great hunger for future mountaineering projects.